Hello, welcome to my artist talk.

This was supposed to be an in-person talk about this show at the gallery but then like most things in the world it was cancelled abruptly.

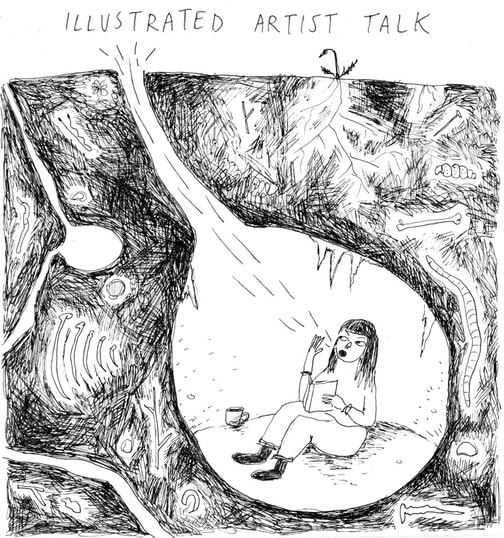

The gallery has been so accommodating and suggested I do it online instead and then I thought because it’s online let’s make it a webpage instead of a video, especially since they already made such a great video and I can’t compete with it. So this is an illustrated artist talk. And it has a lot of words and pictures and links and stuff that you could spend a long time going through or you can skim. Either is good.

Thank you so much for coming.

I will tell you a bit about my practice and about how I got so obsessed with worms.

This was supposed to be an in-person talk about this show at the gallery but then like most things in the world it was cancelled abruptly.

The gallery has been so accommodating and suggested I do it online instead and then I thought because it’s online let’s make it a webpage instead of a video, especially since they already made such a great video and I can’t compete with it. So this is an illustrated artist talk. And it has a lot of words and pictures and links and stuff that you could spend a long time going through or you can skim. Either is good.

Thank you so much for coming.

I will tell you a bit about my practice and about how I got so obsessed with worms.

I went to Emily Carr University and did a BFA and graduated in 2013. I took a ceramics intro class and the instructor said I had a real hand for clay and should stay with it.

I found out later he told that to pretty much everybody in the class but it was too late. I was en route to total ceramics domination.

I think in retrospect I had some formative experiences with ceramics in childhood.

When I was eight we moved from BC to Peru for a few years. My dad worked for a mine there. (Sometimes now I sell artwork to raise money and donate it to protests and legal funds that challenge the activities of that same company and others like it. Growing up under the shade and light of such serious, colonialism-flavoured resource extraction has so many attendant privileges, problems and weirdnesses. It’s complicated and I’m still sifting through it.)

Peru is an amazing place. We lived very high in the mountains. You could walk on a dirt road and find pottery sherds at your feet.

Once there was an archaeological dig close by and my school visited the workshop where they sorted through their finds. I saw a man carefully assembling a pile of sherds into a wire armature, the pot re-forming in front of him.

We went to many many museums where they had a lot of sexy Moche pottery and sculptures which are still to my mind the Most Beautiful and Interesting Objects in the World (especially if you're eight.)

I found out later he told that to pretty much everybody in the class but it was too late. I was en route to total ceramics domination.

I think in retrospect I had some formative experiences with ceramics in childhood.

When I was eight we moved from BC to Peru for a few years. My dad worked for a mine there. (Sometimes now I sell artwork to raise money and donate it to protests and legal funds that challenge the activities of that same company and others like it. Growing up under the shade and light of such serious, colonialism-flavoured resource extraction has so many attendant privileges, problems and weirdnesses. It’s complicated and I’m still sifting through it.)

Peru is an amazing place. We lived very high in the mountains. You could walk on a dirt road and find pottery sherds at your feet.

Once there was an archaeological dig close by and my school visited the workshop where they sorted through their finds. I saw a man carefully assembling a pile of sherds into a wire armature, the pot re-forming in front of him.

We went to many many museums where they had a lot of sexy Moche pottery and sculptures which are still to my mind the Most Beautiful and Interesting Objects in the World (especially if you're eight.)

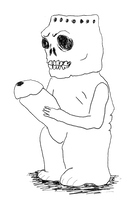

(You can visit the real objects from the animation if you click on them below. Note that the skeleton is identified as a "sexually active inhabitant of the underworld".)

After graduating from art school some ceramic friends and I started the Dusty Babes Collective to stay engaged and share equipment and studio space and sometimes exhibit and sell together. They're amazing, hard-working, inspiring people.

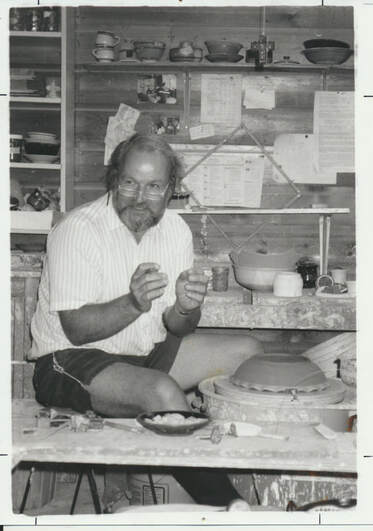

In 2015 Don Hutchinson, a local potter and teacher at Langara College, retired and sold his Surrey (Semiahmoo territory) property to a developer.

He built the studio in 1971 - it's perfect, with two gas kilns and blackberries and cedar trees and yard rabbits.

We've rented the property since 2015 and used it as a communal Dusty Babes studio. It'll be developed sooner rather than later probably but until then we are partying hard.

So far fourteen young artists have had spaces at the studio and many more have participated in open houses and soda firings.

Don passed away in November of 2018, a big loss for the clay community and all who knew him. Below is him working in the studio and his self-portrait I wheatpasted in tribute on the garage door.

He built the studio in 1971 - it's perfect, with two gas kilns and blackberries and cedar trees and yard rabbits.

We've rented the property since 2015 and used it as a communal Dusty Babes studio. It'll be developed sooner rather than later probably but until then we are partying hard.

So far fourteen young artists have had spaces at the studio and many more have participated in open houses and soda firings.

Don passed away in November of 2018, a big loss for the clay community and all who knew him. Below is him working in the studio and his self-portrait I wheatpasted in tribute on the garage door.

My boyfriend and I live on the property in a falling-apart little house that also used to be a pottery studio. I think working at this studio and living here has influenced me a lot. It's so out-of-time and quiet and brown and wooden.

It feels like a race against time because I know it'll be developed soon but it also feels like I'm getting slowly encased in amber. Every nail and twig here has memories, mine and otherwise. It's so fun to share space with friends but it's also very solitary most of the time.

There's also rats.

It feels like a race against time because I know it'll be developed soon but it also feels like I'm getting slowly encased in amber. Every nail and twig here has memories, mine and otherwise. It's so fun to share space with friends but it's also very solitary most of the time.

There's also rats.

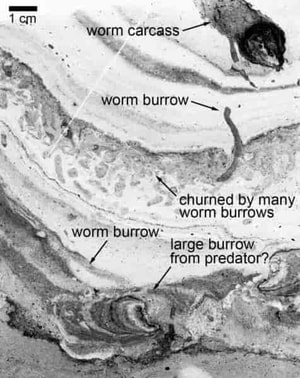

In 2018 I was making a piece called Iron Midden for the Dusty Babes show 'Subject Matter' at the Gibsons Public Art Gallery. (This piece was re-mounted as part of Sister Worm). I was looking up all kinds of information about middens.

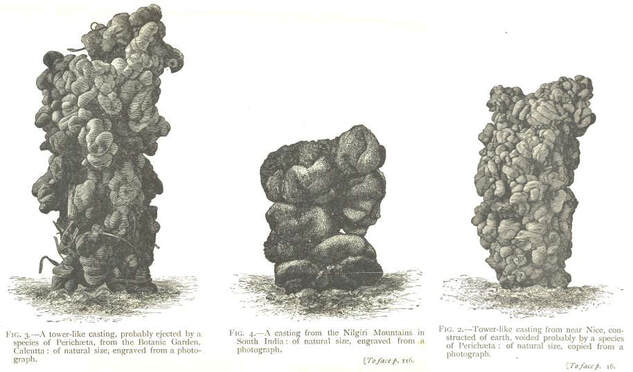

Through that searching I found out that earthworms create middens at the entrance of their burrows - little piles of castings (poop) and whatever other debris they gather.

They pull leaves and stems down into their burrows, sometimes unsuccessfully, leaving a leaf or twig sticking straight up out of the ground. These middens are pretty distinctive once you know what to look for.

Through that searching I found out that earthworms create middens at the entrance of their burrows - little piles of castings (poop) and whatever other debris they gather.

They pull leaves and stems down into their burrows, sometimes unsuccessfully, leaving a leaf or twig sticking straight up out of the ground. These middens are pretty distinctive once you know what to look for.

Searching for worm middens, I found the "micro videos" of Brad Griffiths, who for years has been documenting the nighttime activities of worms in his driveway with the attention, love and patience we generally reserve for newborn infants.

The video below, tenderly captioned in first-person narration from the perspective of the worm, blew my mind.

It had actually never occurred to me before that worms had mouths, much less that they could drag rocks around.

I'm always interested in the vernacular, things that are really common and maybe not noticed but get more interesting the more you look for it: the seedy underbelly, the backstory, the hidden detail, Behind the Music, ten tabs deep on Wikipedia. And I eat facts and information, like just gobble it up.

In the documentary With My Back to the World, the painter Agnes Martin, then 90 years old, says something amazing:

“There’s two parts of the mind you know. The intellect: the servant of ego. It does all the conquering and all that darn thing. The intellect, it’s a struggle with facts, you know like the scientists, they discover a fact and then they discover another fact and it’s related and then they make a deduction from all these facts. Well in my opinion that is just guesswork. So completely inaccurate. You’re certainly never going to find out the truth about life, guessing about facts. I gave up facts entirely, in order to have an empty mind. Or an inspiration to come into. I mean if your mind is full of garbage, if an inspiration came you wouldn’t recognize it anyway. So you have to practice a quiet, empty mind. I gave up the intellectual entirely. I had a hard time giving up evolution and the atomic theory but I managed it.”

I love Agnes Martin. I feel guilty about being such a fact-gobbler. But I'm really not a spiritual or still person so information and facts and making up connections between them is kind of my way to get there.

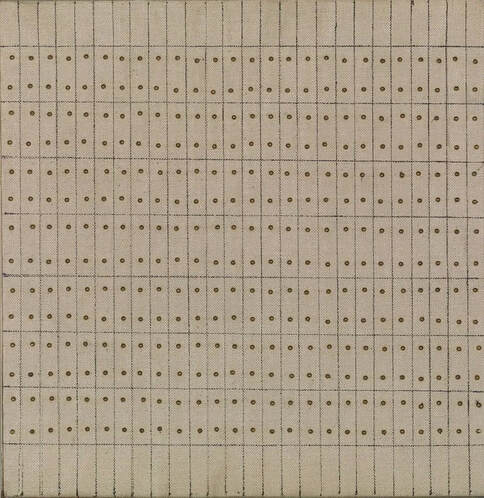

Worms work all night tugging on leaves and nudging rocks around. Slime molds bubble away, mites eat and dig and eat and dig - once you notice the particular rhythm of that kind of activity you see it everywhere - Agnes Martin tapping hundreds of tiny nails into a canvas, Ruth Asawa weaving and Viola Frey pinching pinching pinching. I don't find that activity meditative or calming or tedious, just really - natural and normal. You do it until it's done.

Reading can be like that too, chewing your way through a book. I started reading a lot about worms and collecting facts.

Did you know that worms can live to be eight years old? Did you know earthworms are invasive to North America, and they move further north every year because of climate change? Worms form herds and make group decisions. We live above a 500-million year old worm superhighway. Darwin played music to worms and concluded they didn't care. Did you know worms once saved the world?

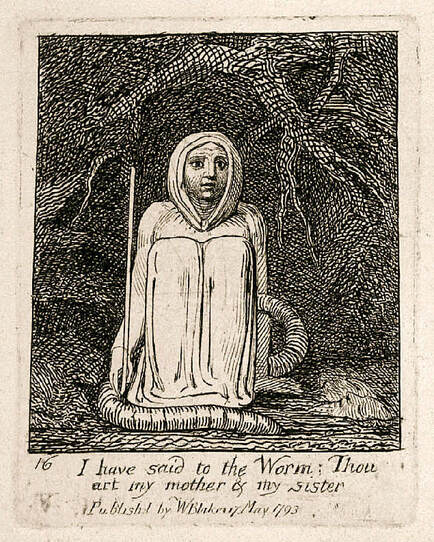

I found art about worms too. Octavia Butler. Jenelle Schwartz writing about 'vermiculture' in Romantic literature. The Blaschkas made many glass models of different worm species. William Blake really came through.

Blake's poem Book of Thel, published as an illuminated manuscript within the larger work Songs of Innocence, has a young maiden (read: teenager) stomping around complaining that life is useless because it will end.

She converses with a personified Lily and then a Cloud, who introduces her to the Worm and the Worm's guardian, the Clod of Clay. She coos over the Worm for a while and then the Clod of Clay invites Thel to visit her home, the underworld.

Thel gets down there and has a look around. She sees the roots and dark valleys and her own grave and then hears a voice of sorrow and has enough. "With a shriek/Fled back unhinder'd till she came into the vales of Har." (4.22).

Darkness and revulsion and grossness are definitely part of looking into the underworld, even if you're the earnest type like me.

A lot of the academic writing about dirt likes to argue that dirt is a construct (sure) and society has become hysterical about hygiene because we're secretly all perverts (basically).

I really went in for this idea until some time around two weeks ago when I found myself disinfecting a bottle of disinfectant. We're now actually being ordered to be hysterical about hygiene and the really horrifying thing is it's not even enough.

So the dirt argument will have to be revisited.

Dirt and death and worms are all linked of course. This is William Bryant Logan on worms:

"The horror at these beasts is perhaps fundamentally sourced not simply in their habits but in the fact that they colonize the dead...yet the worm is undeniably necessary. It hoards and guards treasures. He is a sort of banker of the fairy-tale world, though he makes it difficult to effect withdrawals. He is in this respect the representative of the dark side of metamorphosis."

I really went in for this idea until some time around two weeks ago when I found myself disinfecting a bottle of disinfectant. We're now actually being ordered to be hysterical about hygiene and the really horrifying thing is it's not even enough.

So the dirt argument will have to be revisited.

Dirt and death and worms are all linked of course. This is William Bryant Logan on worms:

"The horror at these beasts is perhaps fundamentally sourced not simply in their habits but in the fact that they colonize the dead...yet the worm is undeniably necessary. It hoards and guards treasures. He is a sort of banker of the fairy-tale world, though he makes it difficult to effect withdrawals. He is in this respect the representative of the dark side of metamorphosis."

Even though an earthworm is so familiar and harmless, they are are still representative of the underground and well capable of inspiring a shudder.

In "Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Plantationocene, Cthulucene: Making Kin", Donna Haraway writes:

"Renewed generative flourishing cannot grow from myths of immortality or failure to become-with the dead and the extinct...I am a compost-ist, not a posthuman-ist: we are all compost, not posthuman."

Haraway also says:

"Ancestors turn out to be very interesting strangers; kin are unfamiliar (outside what we thought was family or gens), uncanny,

haunting, active."

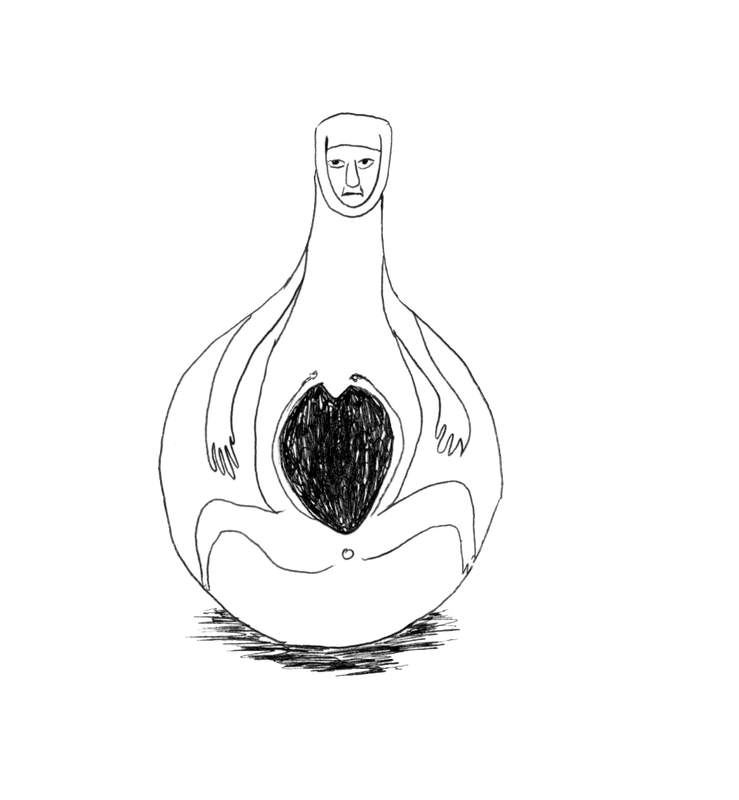

So the pieces I made for the Sister Worm are generally about that - looking for kin, looking in history, talking to worms. Most have some specific fact or story behind them - I think the gallery's video covers those pretty well so I won't mention them here.

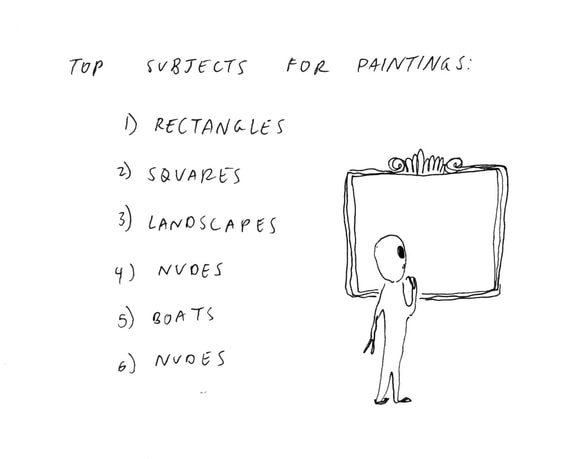

I think a lot of the pieces are about clay, but in the same way that most artwork is about its medium. If I was an alien and came to earth and looked at all the paintings in the European museums I would deduce that artists are obsessed with rectangles. Most paintings are 50% about canvas and 50% about whatever the image is.

I think a lot of the pieces are about clay, but in the same way that most artwork is about its medium. If I was an alien and came to earth and looked at all the paintings in the European museums I would deduce that artists are obsessed with rectangles. Most paintings are 50% about canvas and 50% about whatever the image is.

(I am just a potter being cheeky, not somebody who actually knows anything about painting.)

Clay is my ideal medium - it has a voice of its own but it's a wonderful mimic too. It's food and flesh and dirt and positive and negative.

This is what William Bryant Logan says about clay:

Clay is my ideal medium - it has a voice of its own but it's a wonderful mimic too. It's food and flesh and dirt and positive and negative.

This is what William Bryant Logan says about clay:

"Inert matter! As if there were ever such a thing. Beauty is the vocation of the world.

Under the electron microscope, one can perceive the intricate harmonies of clays.

A Hawaiian imogolite clay looks wilder than the lava fields at Mauna Loa. It is a labyrinth of tubes into which molecules disappear.

A Chinese kaolin is more complex than the karst mountains of which Li Po sang: its particles are long hexagonal bars, piled side by side; millions of parchment sheets, each curled slightly at the edge.

An Iowan kaolin is more gnarled than a bluff along the Mississippi. Its hexagons stack like ancient limestone formations. A particle of an ilmenite from Missouri looks like fireworks, or like the corona of the sun during an eclipse.

A Spanish illite curls back like the tongues of cats. The montmorillonites of Arizona and Wyoming resemble dense growths of watercress. Here is one like a cupboard full of plates, another like a bowl full of needles, a third like the capillaries of the lungs.

The assemblies of the clays are like those hedge mazes and forests in which fairy-tale children become lost, like those places where the old woman is met and where treasures are won. The landscape of the clays is like the wall of the stomach or the tree of the capillaries, or the intricate folds of the womb. It is the honeycomb of matter, whose activity is to receive, contain, enfold, and give birth.

My favourite medieval saying is about Mary the mother of God. 'What the whole world could not contain,' so it goes, 'did Mary contain.' There is more real sex in that one sentence than in all the so-called erotic literature ever penned. And it is exactly about the principle of matter, whose activity is fully and willingly to receive."

Under the electron microscope, one can perceive the intricate harmonies of clays.

A Hawaiian imogolite clay looks wilder than the lava fields at Mauna Loa. It is a labyrinth of tubes into which molecules disappear.

A Chinese kaolin is more complex than the karst mountains of which Li Po sang: its particles are long hexagonal bars, piled side by side; millions of parchment sheets, each curled slightly at the edge.

An Iowan kaolin is more gnarled than a bluff along the Mississippi. Its hexagons stack like ancient limestone formations. A particle of an ilmenite from Missouri looks like fireworks, or like the corona of the sun during an eclipse.

A Spanish illite curls back like the tongues of cats. The montmorillonites of Arizona and Wyoming resemble dense growths of watercress. Here is one like a cupboard full of plates, another like a bowl full of needles, a third like the capillaries of the lungs.

The assemblies of the clays are like those hedge mazes and forests in which fairy-tale children become lost, like those places where the old woman is met and where treasures are won. The landscape of the clays is like the wall of the stomach or the tree of the capillaries, or the intricate folds of the womb. It is the honeycomb of matter, whose activity is to receive, contain, enfold, and give birth.

My favourite medieval saying is about Mary the mother of God. 'What the whole world could not contain,' so it goes, 'did Mary contain.' There is more real sex in that one sentence than in all the so-called erotic literature ever penned. And it is exactly about the principle of matter, whose activity is fully and willingly to receive."

Thanks for coming to this artist talk! I really appreciate your time and patience with this new format. And thank you to the Seymour Art Gallery who have been so supportive throughout the whole exhibition process and to Liam O'Brien for helping build this page.

Here are some answers to questions submitted earlier. And underneath is a form you can use to submit a question if you like.

“Are you questioning hierarchies of materials/firing techniques or was it merely aesthetic?” -Sam K

I'm guessing this is especially about the Six Girls pieces - yes! It's kind of like an inside joke but I thought that putting an earthenware sculpture on a soda-fired pedestal was pretty funny. I don't like any purity narrative or heirarchy - what really bugs me is when historical ceramics are seen as less advanced because that culture didn't have glaze technology. The technology to make burnished ware and a palette of slips and pots without a wheel is totally impressive and sophisticated too.

“Will the worm brain go on indefinitely? Not sure of its power source or exactly how it works.” -Barb P

Yes! (This is the worm brain). As long as it's plugged in and turned on - it just draws power from a regular socket. It doesn't have a cycle or routine - it just acts and responds in the moment.

“I’ve always been fascinated by a worm’s circulatory system, do you know much about it?” -Maddy E

Not a lot. I know that they have five aortas which are called 'pseudo-hearts'!

"Would you consider doing more claymation and illustration/animation in the future based on your experience with this artist talk?" -Laura C

Yes! This was kind of an experiment in a couple different methods - I would like to try more. Claymation opera?

“How did you get the worms to look so real?” -Barb P

Worm-making tutorial: